I’m intimidated by writing about RPGs. I have a deep-seated belief that everyone is playing every game so completely differently that valuable insight is hard to come by. The characters we inhabited, the choices we decided to make, the way the world was interpreted– if its all so singular and unique, what does my commentary say about the game itself and not me? So this is Inhuman Conditions, an oblong box meant to look like the carry-case of a retrofuturist interrogation device, here to bridge the gap between RPG and board game. What does this thing say about me?

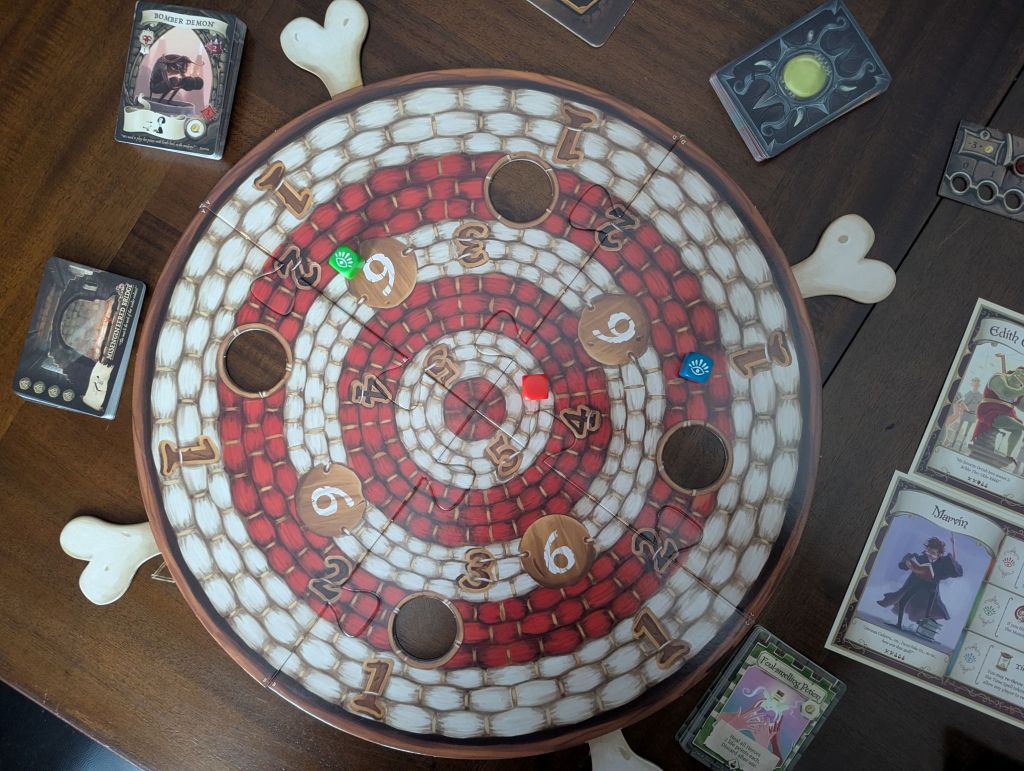

Inhuman Conditions is a roleplaying game for exactly two players that takes strong inspiration from Blade Runner. In the game, one player is administering a test to determine if the other player is a robot. The subject is either a human, a robot trying to pass as a human, or a robot trying desperately to misbehave enough to break their programming and murder their assessor.

In Tom Vasel of Dice Tower’s review of Inhuman Conditions, he argues one of his major complaints about the game: if you are being interrogated, and are in fact a human, it is too easy to be a human. His point boils down to– and I’m not in total disagreement with him here– just act normal. If you can act normal, you win, so normal human behavior: engage. Roleplay humanity to someone whose job, at that moment, is to roleplay “be suspicious the person in front of you isn’t human.” He argues if you do get dealt the “human” role, the game is too easy, even boring.

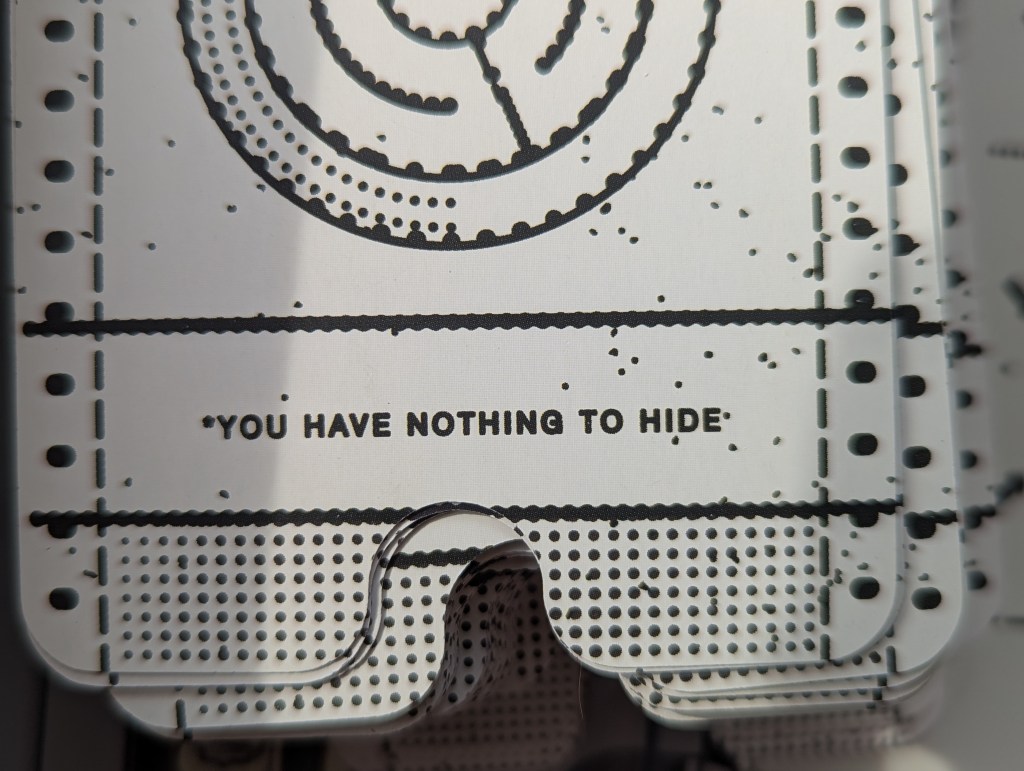

Just don’t do anything that might be considered suspicious or “weird” while maintaining a conversation for five minutes. That’s… easy? Right? Look, I’m a human and have nothing to hide. I’m indignant about having nothing to hide, not because I have something to hide, damn it, but because I’m Chet the Janitor and I was just doing my job before getting dragged into this interview. I don’t know a thing about being a robot, because being a human is all I know. And even if I were a robot–

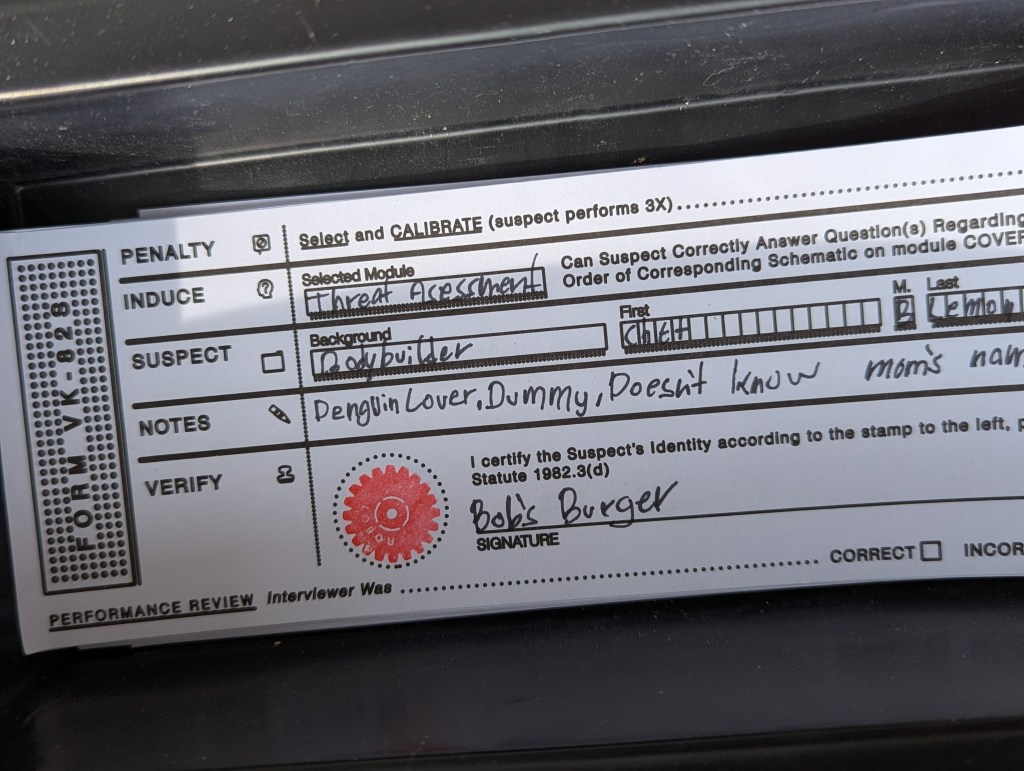

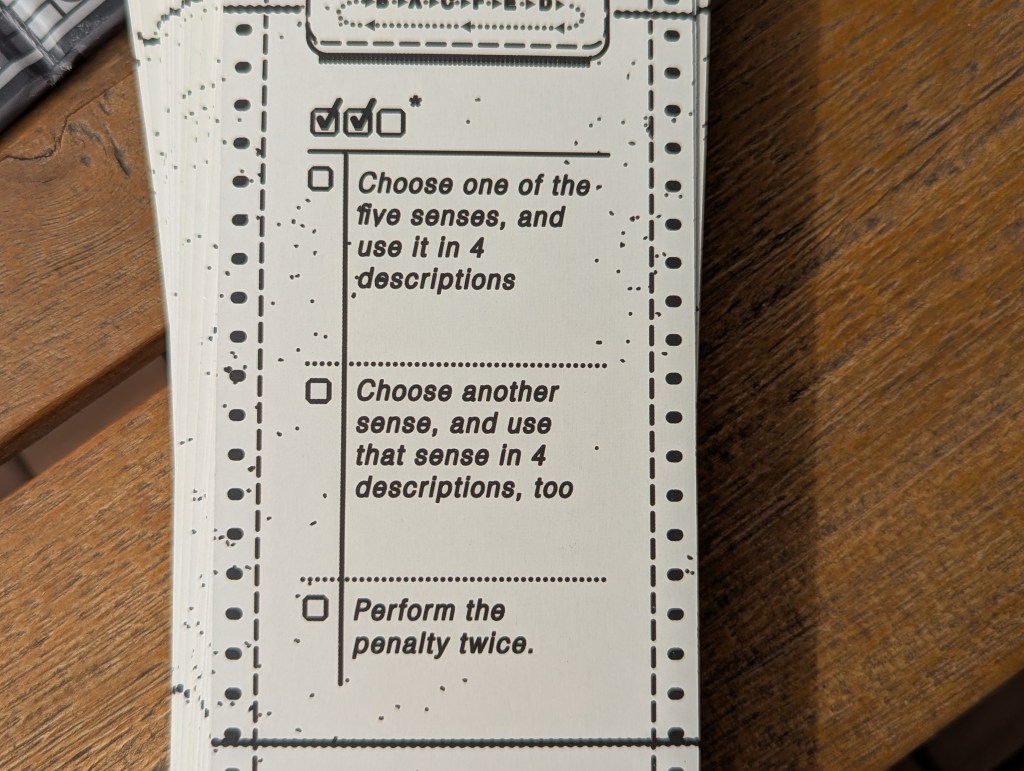

The interview starts off with a series of protocols that is both a tutorial for what the game is going to be and a pseudo character creation. Before the assessment can begin proper, the subject/target/second player must pass an arbitrary quiz, answer some questions about their name and occupation, and agree to some terms. This establishes what the rules will be for the ensuing five minutes, a chance to meet who your partner is playing today, but also the game has already began. You are now being interrogated, before the timer has even started. The robot knows the answer to the quiz but may choose to feign struggling (or spend the time memorizing their required quirks), while the human will have to put in effort to solve a little maze.

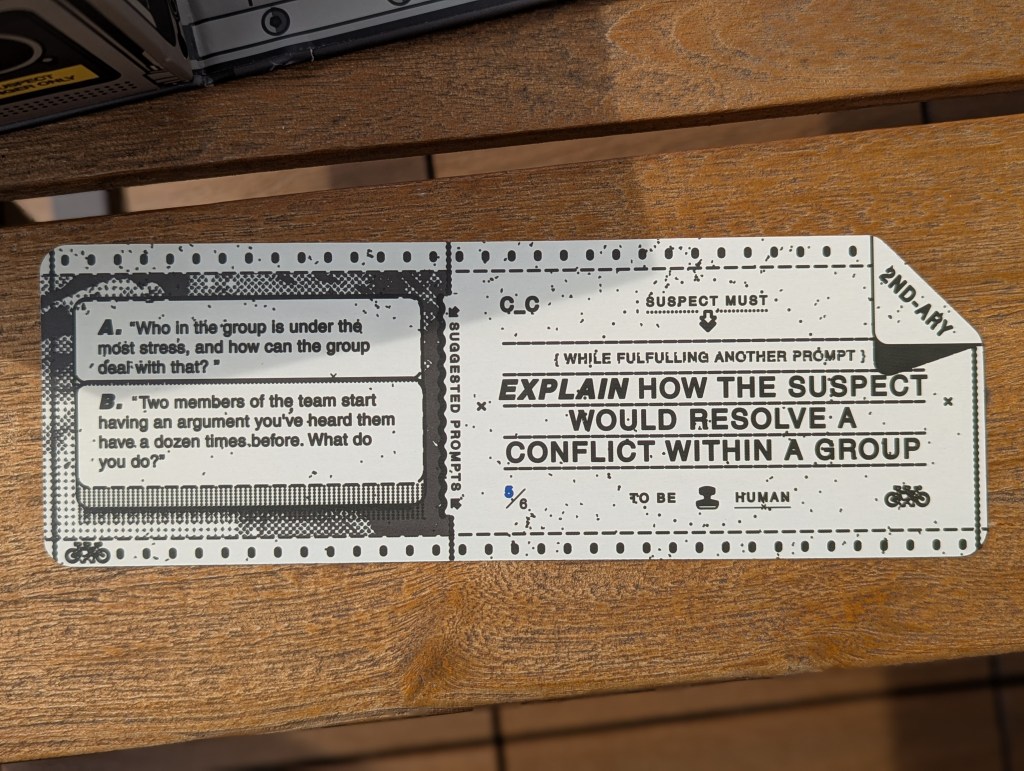

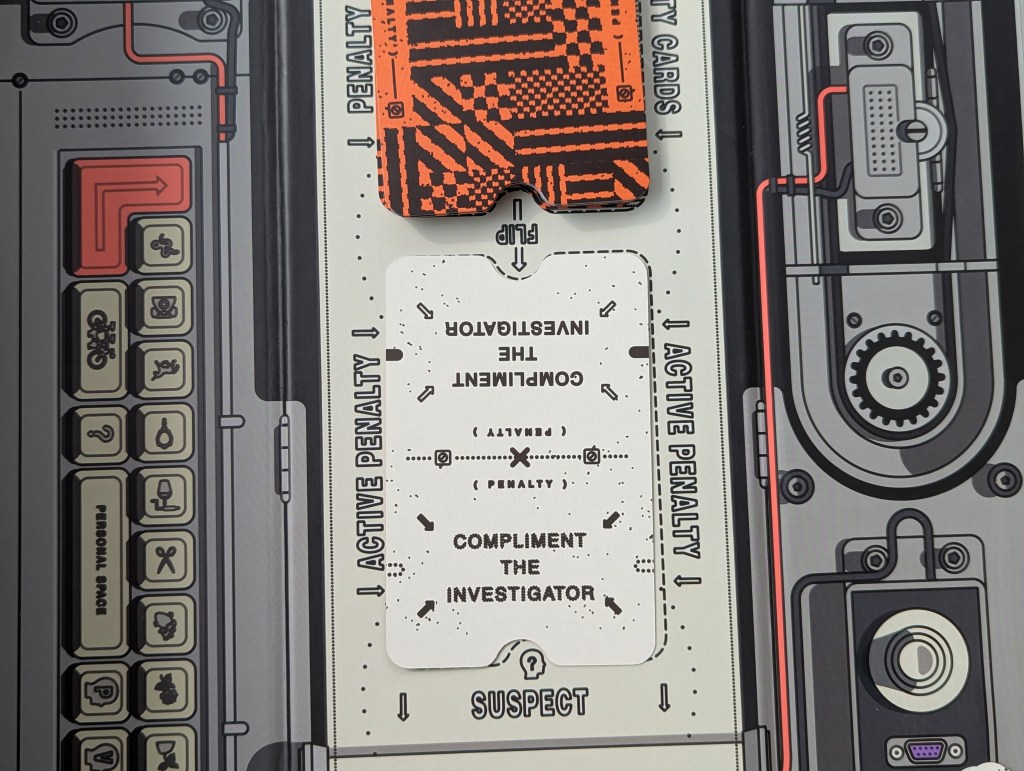

Once the two players have agreed on what they will be discussing today (empathy, small talk, aspirations, y’know, human stuff) the timer starts and the Investigator has five minutes to determine who they are talking to. At the end, if they haven’t been murdered by a vengeful robot, they stamp their determination on a little sheet. If the Investigator lets a human through, both parties win. If they let a “patient” robot through, the robot wins. If they prevent a robot from, I guess, going about their daily life after this meeting, the interviewer wins.

This interrogation is a legally-distinct Voight-Kampf test, yes. As the Investigator, you will be asked to analyze your friend’s ticks and nervousness and wonder about their authenticity. You will be forced to question whether their ineptitude, their slip-ups, their inability to stay in character, are natural or prompted. At any time, as the interviewer, you can end the conversation and stamp your “opponent’s” fate. How much grace are you willing to give them to bumble around, avoid your questions, get into character? Is their “clearing their throat awkwardly and asking how much time is left” an attempt to, god forbid, kill you?

While Inhuman Conditions can sometimes be raucous, silly, casual fun, it can also be a paranoia simulator. As the Investigator, you are put into the shoes of someone who has to be intensely suspicious of your victim: a cop, through and through. Treat them as alien, have them play up every weird facet about themselves– if they have a flaw, or seem like they don’t belong in any way, get them to repeat that behavior and throw them in robot-jail.

As the subject, you become hyper aware of what you’re doing. The game provides you with an occupation as its only guidance for who you are. The simple character you devised to roleplay as in 30 seconds, Bink Bint, a child actor known for various roles in situational comedies and who filters everything through the films they’ve been in, well, they better button up. When Bink Bunt mentions his feature films the seventh time and the cop on the other side starts to think Bink Bunt isn’t allowed to mention the real world at all, you better impromptu make the character you are playing more… human.

Roleplay more, better. Stop roleplaying so much.

Do something. You have, like, two minutes.

I don’t think this game is for everybody. Some people will be uncomfortable roleplaying as the very-much-cop role, and others as the very-much-oppressed role. I have, at least once, found it easy to “roleplay” genuine discomfort and indignation at being suspected of doing things and being a thing that I was not. For me, the added layer of roleplaying and improv makes the deception palatable, whereas other social deduction hidden role games leave me cold. Maybe it says something that I would rather roleplay as a balloon animal artist being persecuted for accidentally complimenting my friend than get betrayed by that same friend in Secret Hitler.

While the game can be a pressure cooker of intense roleplay, that isn’t the only experience this game facilitates. As this is a roleplaying game, the people you play it with and the way your minds connect will, ultimately, decide how each match goes. Will each round spiral further and further into in-jokes, as each character is revealed to be a sibling of the last 6 characters you played as? Will you, as a robot, show up to the interview playing it cooler than cool, and dare your friend to throw the biggest chiller ever made into the slammer? Maybe you will play it straight one round, and then bring out one of those silly characters the next. That’s not only fun, it creates a meta-game around the game, and can be a strategic advantage in repeat plays. Like any roleplaying game, comedy and goofing off with your friends is always an option, even if one of you is a nervous wreck trying desperately not to get canned.

But I do recommend taking the game completely serious at least some of the time. Try to win, yes, but get into character. The whole experience, the aforementioned oblong box, is littered with detail and theme to immerse you, so it would be a shame not to give in at least once. If roleplaying is a bit too cringe for your board gaming sensibilities, your time is probably best spent in some other two player game. My partner rates this as one of the worst games I have ever subjected her to. I get it. It’s a nerdy thing to get into, possibly too nerdy for some.

If you are thinking this game might possibly be for you, then I have good news. This game, despite its two lavish, prop-heavy productions, has a comprehensive print and play. It has even been adapted to be playable over video chat, if that’s your kind of thing. Designers Tommy Maranges and Cory O’Brien have made a brilliant game and are giving it away for free if you have a webcam and/or a printer. The real-deal product is nice, though. The pictures I have are of the first edition, so I can’t speak to the quality (or availability) of the second edition, but the whole thing is cool. It also comes with two (2) really nice stamps, and these props are a delight to use on the forms and everywhere else, honestly.

Speaking of which, I am choosing to give this game the coveted Human stamp of approval. It’s the highest honor I can bestow, as it means the game won’t be getting sent to the robot-grinder.

Leave a reply to rid Cancel reply