In word games, being the “clue giver” is always the harder lot. It is the clueman’s job to come up with masterful strokes of vocabulary that cut through the dense foliage, to offer something so breathtakingly clever to place their team in exactly the right place. It is their job to lead their team, the metaphorical horse, to water. In Landmarks, as in life, it is not possible to make them drink, nor keep the water jug intact.

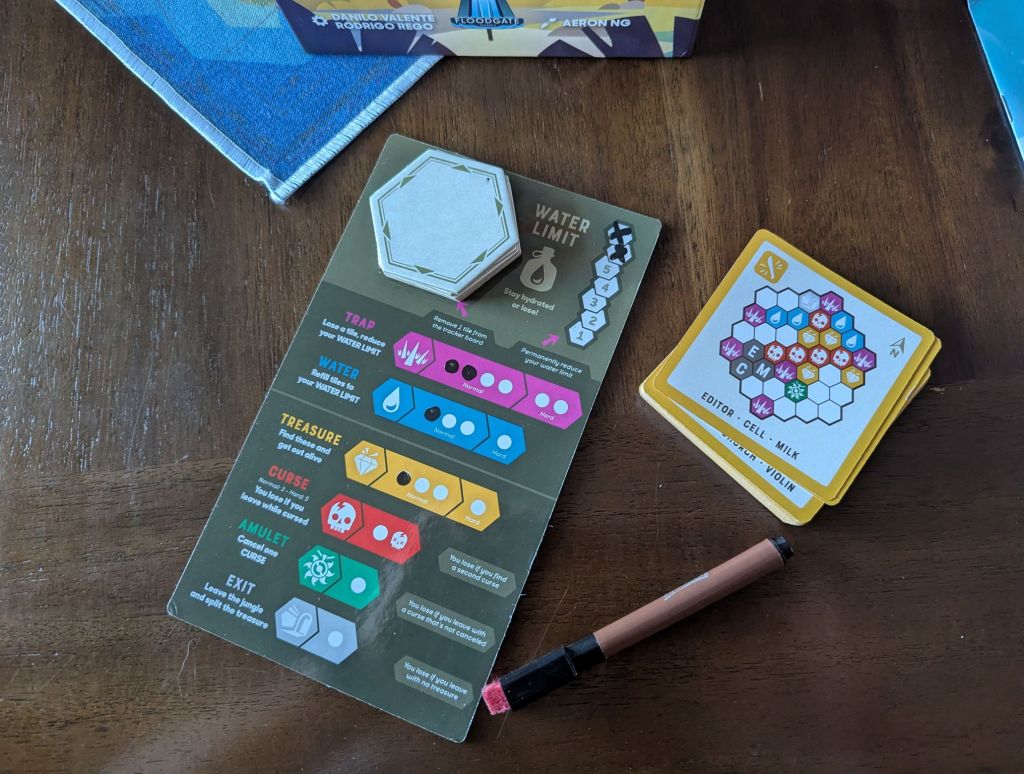

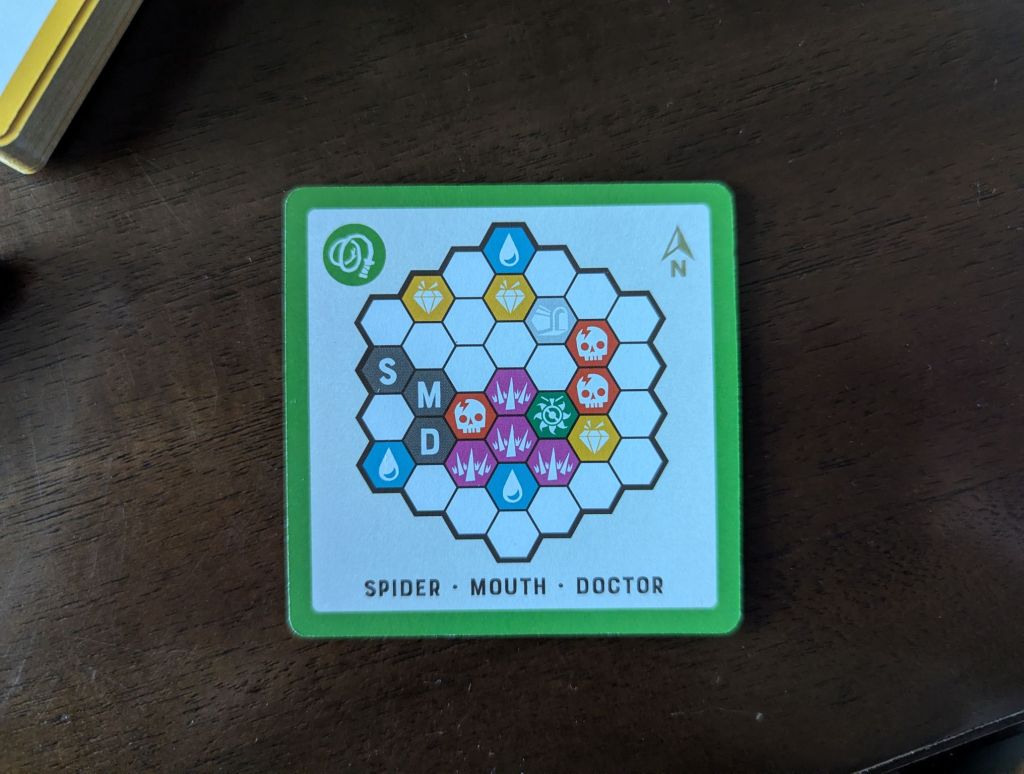

Landmarks is a cooperative (or optionally competitive) party game by Rodrigo Rego and Danilo Valente. In the base cooperative game, one player acts as the pathfinder. They are given a map of hexagonal tiles containing traps, water sources, jewels, curses, an exit, and a couple tiles marked with words. The pathfinder’s job, then, is to provide a word which branches off the starting web of word tiles towards the good locations: water for more tiles, treasure for points, and the eventual exit to secure the win.

They provide the word, the other players (“the party”) decide where the word goes based on its association to the existing words, then the navigator reveals what they found by placing the tile on that spot. This may seem straightforward, even easy, but it rarely is.

Your initial impulse may be to give synonyms to coax your team into the exact spot you need them to be. This works once or twice. But then you’ve created a nest of words synonymous with “meeting”, so getting your team to branch out in specific ways from that cluster is difficult. Tricky. Giving so many good, obvious instructions can come back to bite you– I like that. Maybe synonyms aren’t the way.

To make things worse, cutting a path through Landmarks’ map is frequently not as simple as “go to good tiles; avoid bad tiles.” There is some deliberate ambiguity about what constitutes a victory (which essentially boils down to how many treasures you will be happy to leave with), but you always need one treasure. You also always need an exit. Maybe you’re willing to walk your team into a trap or two knowing you can get them to an oasis next turn, if you’re so brave. Perhaps your team will think, instead, they placed incorrectly and internalize the (wrong) need to turn around and head elsewhere.

Landmarks works different parts of your word-association muscles, too. Sometimes, you need to come up with the classic “what is one word which perfectly connects these three words”. In fact, the Floodgate Games BlueSky page posts a daily Landmarks puzzle of exactly that. But, in truth, I rarely find myself in those situations. Instead, I am puzzling over how to best connect two words while completely disconnecting a third– or how to connect to one word while making it clear I am not referring to its synonym right next door.

If you are not the pathfinder, you unfortunately are playing a less interesting game as “the party.” While the pathfinder comes up with clues, navigates a tricky map, and weighs the risk of stepping on a trap, the guessers are blind. They place the tiles more or less where the clues lead them, unaware of any grand strategy. It can be a good time as the party laughing at the miscommunications or getting excited at your amateur mind-reading, but it feels like a lesser experience.

Unfortunately, there are also many times when the party are made to guess. If I’ve intuited my clue-giver wants me to venture out from a hex– let’s say east away from the rest of the tiles– well I actually have a couple choices of where to travel to. Even with a perfect hint I may still, as the guesser, be subject to a bit of a 50/50. I think this is okay as far as adding difficulty to the game and it even makes sense thematically. But if I’m already playing the role which does not interact with half the game, I would like all the agency I can get.

I wish both roles were equally good, especially in larger games where one pathfinder might be influencing three or more people.

When the map takes shape, though, it is hard not to smirk and marvel at your work regardless of your role. Word association is a good time, but it turns out to be even better when you’re left with a record of the places your minds went. Admire the map of your collective neural pathways, showing how “Miami” and “football” conjures the thought “dolphins”. In the end, the map also serves as a gateway into a (usually funny) conversation over where exactly our wires got crossed and how we went about uncrossing them.

Even if I have my gripes, this game’s “one more go” factor is very high. After you’re done conversing on how badly a clue was misinterpreted, you will want to hop back into another round, roles reversed, to prove you can play one side better. If you flunk out early by getting double-cursed (a real failure condition), the desire to shuffle up and go again temporarily overrides any concerns of rules or victory ambiguity. For that, I recommend Landmarks, albeit with a couple caveats.

Leave a comment