Imagine, if you will, a creature. It is roughly the size of a mouse. Its body is covered in a rock-hard defensive carapace. Beneath that solid armor, which I’ve chosen to imagine clanks around noisily and unevenly like an ill-fitted set of hockey pads, is yet another layer of plating. It is less mammalian and more, let’s say, brick-like.

Now imagine there are hundreds of this animal. They have shown up to an arid watering hole not to forage on the greenery or hunt (it is, after all, smaller than the other animals) but to scavenge on the remains of another creature’s successful hunt. Is this the ultimate lifeform? Does this amalgam of chitin have any peer? That’s what we are here to answer.

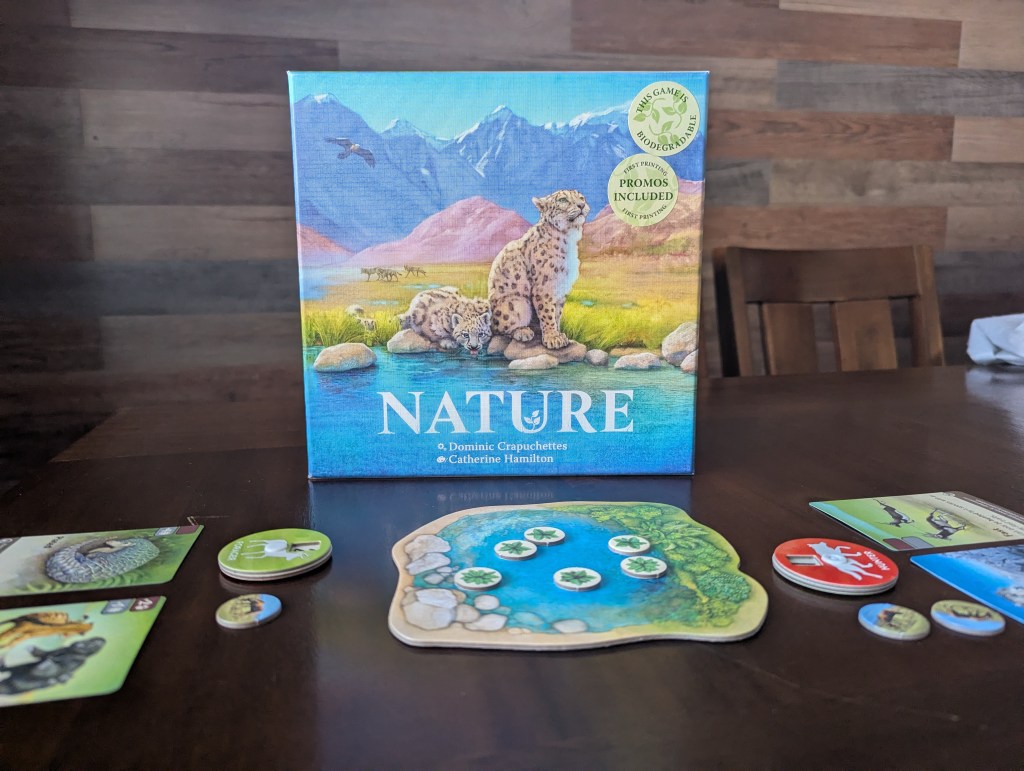

Nature is a 1-4 player board game by designer Dominic Crapuchettes and studio North Star Games. In it, players will be steering the course of natural selection (don’t call it artificial) to produce the most successful species over the course of 4 rounds. There are a number of different modules which can be mixed and matched to expand the scope of Nature, but this review has been written after exclusively playing the base game.

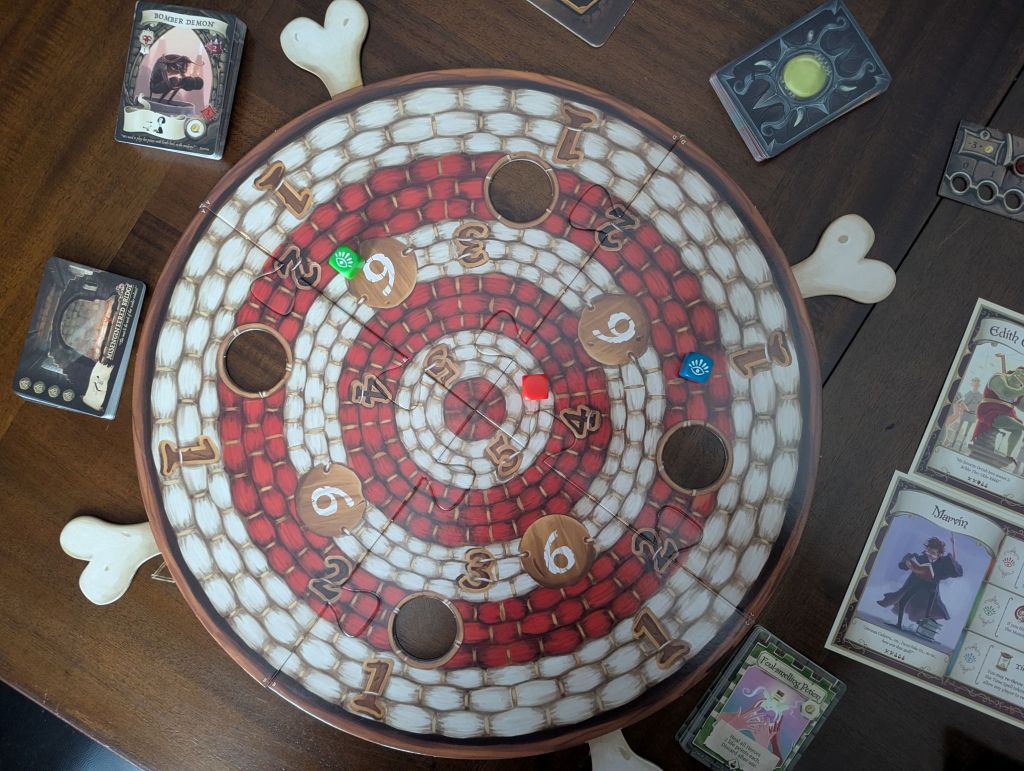

Each round, players will be given a new species to look after. In the first round, this is a nondescript mouse-sized herbivore with a nascent population. The goal of Nature is to have food in your animals’ bellies at the end of each of these rounds. There is a watering hole which refills with food each round, but there is unlikely enough plants to satiate everybody. The game, then, lies in your ability to adapt and make sure your species get theirs.

Each round you draw five cards. Cards can be discarded to make your animal larger, thereby giving them an advantage at muscling their way to the tastiest leaves. You may also discard a card to make your population larger– more mouths to feed means more food you can score inside bellies. Or you can play these cards face down as traits, evolving your animal with useful new characteristics. Once everyone’s played out their turn, traits are revealed and species takes turns foraging or hunting (I’ll get to hunting, don’t worry).

There is a relatively small set of traits, but each of them are unique and worthwhile in the right competitive environment. A Tusked animal gains the ability to eat some meat (an omnivore!) whenever the watering hole becomes empty–perfect if other animals are being greedy. A Clawed animal is just that, greedy, able to grab more food and feed more of their population at once. The most warping of these traits (and they’re all very distinct) is the ability to forego foliage altogether and convert your species into a hunter.

Predators use their size and traits differently. They hunt the other species at the table, turning rival populations into meat. Unlike other traits which must be drawn and played secretly, any player can make one of their animals a hunter at any time during their turn, but they must do so publicly. Declaring yourself a hunter takes up one your animal’s three allotted traits, but it could be worth it for access to an all-new food source.

The entirety of Nature is tightly wound, a box-sized hadron collider of player interaction and pressures. The Fast trait makes you immune to any attackers who aren’t also as Fast– but is useless otherwise. An animal with two Fast traits is probably perfectly safe for now, but a knowing predator can likely adapt if they specifically want you for dinner. Going first in a round is great, it means you will get first dibs when it’s time to forage. It also means you have to make all of your decisions before you know if anyone is making the pivot to red meat. If you have a hungry predator with no opposing species to eat, you don’t have the option to simply let them starve– they’ll have to start turning and eating your other animals, if they can.

Nature models competition incredibly well, and consequently is very competitive itself. There are turns which feel like something that could’ve genuinely happened in the animal kingdom, with your human meddling producing something organic-feeling. As cutthroat as Nature may sound, with its only-sometimes-open economy and its “can you eat me/can you not eat me” binaries, I would argue it isn’t brutal or even mean.

Whenever one of your animal population tokens die, whether from starvation or being turned into food, that population is rolled into the species you are given next round. Whenever a species of yours is wiped out, gone from the treadmill of evolutionary history, its body size is also rolled into that next species. Even the traits you invested into it are fully refunded back into your hand. If someone invents a tiger to kill your elephant, your next species will come back as an elephant-shaped blank slate. On a meta level, you lost some points. But textually, the circle of life continues. More animals show up at the watering hole the next day, evolved to handle what your last creation could not.

What I’ve really enjoyed about Nature is how there’s so many opportunities for unique challenges to arise. Challenges not from the game prescribing them, but from other players creating them. The systems are simple enough that, if we were all to cooperate, we could maybe find some way for everyone to more-or-less get fed. It’d be a puzzle, but we could do it.

But when someone creates an army of foraging machines, the ecological niche for “bloodthirsty predator” necessarily opens up. Every round, new animals show up that are going to need to find ways to stretch roughly the same amount of food thinner and thinner. It becomes a puzzle to find where your species can fit into the ecological landscape. Will you create the beautiful plated scavenger mouse? The fastest rabbit of all time? A horned elephant that promises mutually assured destruction? Whatever you create, your opponents will have to prey on your weaknesses or stay out of your way.

On one hand, Nature feels like the genuine article; a family-weight simulation of natural selection showcasing how animals put ecological pressure on one another. At the same time, Nature feels like a gamer’s game, a bundle of tight mechanics chosen exclusively to invite close competition. It is a tight rope beautifully balanced.

In a way, Crapuchettes’ background explains Nature’s successes in both realms. He spent time as a Magic the Gathering pro and then years honing entire games and expansions about evolution. Then, he turns to Nature, an attempt at renegotiating and reinvigorating an Evolution series that had gotten too unwieldy. It feels almost (excuse the pun) Natural for exactly this game to come out of that process.

I could go on but you get the point. Nature is great. The whole thing comes together in a reasonably sized and eco-friendly package; fully expandable with new content that I will definitely get eventually. Maybe when that times comes, when I want more succulent tree-stars to sink my teeth into, I will review a module or two.

Leave a comment