Back before Twitter was unusable, people would post something along the lines of “the food in Studio Ghibli films looks so good” and get, like, ten thousand retweets. And then next week you’d see it again, posted (presumably) for the people who had missed it the first time. Rinse and repeat. It was indefatigable, undeniable, a universal truth. You want to eat those eggs the anime guy is cooking; you know it’d be the best eggs you’ve ever had.

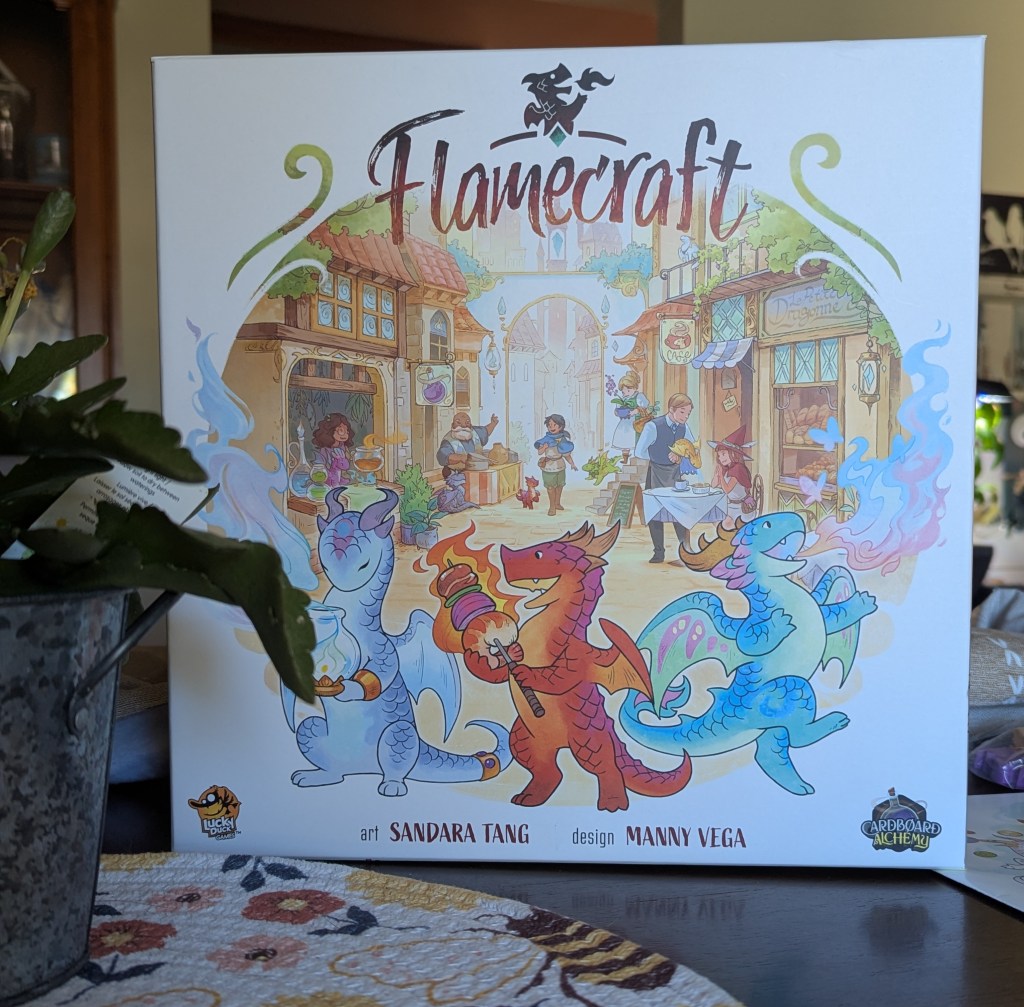

That’s how I feel about the art in Flamecraft. The foods being prepared by these cute little dragons looks so inviting, the potions so potable, the shops so comfortable. Flamecraft’s world emanates a gentle warmth, provided primarily by Sandara Tang’s watercolor illustrations. How can you resist little crystal dragons putting together a bracelet or purple potion dragons making latte art? My god, it’s almost too much.

But let’s talk about the gameplay, too. Flamecraft is a euro game for 1-5 players about contributing the most to an up-and-coming town. At the start of the game, six shops are open, each providing a few of the game’s goods: bread, meat, metal, leaf, potion, and gems. On a players turn, they will visit one of these shops (worker placement style), gathering the goods that shop produces, probably adding a new artisan dragon to it’s staff, and then “firing up” a dragon there. Points are primarily scored by cashing in a set of these items– maybe 4 meat and 2 gems– to permanently upgrade shops with Enchantments.

There is a spirit of semi-cooperation in Flamecraft, even if it is a competitive efficiency puzzle. By placing new artisan dragons or enchanting a shop, you are “engine building” by making that shop more efficient when visited later. Unlike other games where your own personal engine gets to sputtering and converting items to points for you personally, all shops are available to all players. In fact, you can’t visit the same shop twice in a row, so often the fancy new upgrades you’ve made to the local plant nursery will be utilized by others first.

I do hesitate to call this a worker placement game, also, because each player has one worker and there isn’t really “blocking” to speak of. If I’m at the spa, you can stroll on up and get some metal, no problem. Your only penalty is having to give me one of something from your inventory, which again makes this feel… nice. I know I’m supposed to be competing with the other players, but I feel some ludonarrative weirdness between this competition and the world I am playing in. If we are all in this together, if bumping into your friend at the store means giving them a nice gift of leaf, uh… why are we trying to beat each other? Shouldn’t we be working together to make sure these dragons are being paid well, the city is thriving, the lattes are up to standard, etc. etc.? Am I supposed to believe that competition is the best driver of the cutesy dragon treats and potions economy?

Beyond the competition feeling a bit bland, there are a lot of clever bits in Flamecraft. For how much table presence it has, the game is very streamlined. Enchantment cards are little shopping lists you can spend your action turning in. But instead of just dumping resources for points, you get to visit a corresponding shop and “fire up” (use) every critter there.

Each artisan dragon type has a corresponding action: bread dragons draw cards, meat dragons place cards, leaf dragons give gifts for victory points. If I enchant a fully staffed bakery, maybe I’ll get to do all 3 of those actions all at once– as a reward for doing the thing I need to do to get victory points anyway.

Those turns are explosive and satisfying. To me, they also avoid the problem some games have where, once engines have been built, turns get more and more complex and needlessly long. An enchanting turn is definitely longer and more thinky than an early game gathering turn. I found these enchanting turns to never take too long, though, as each shop can only hold 3 dragons, and nothing combos out into infinity.

Another of your point-scoring options are the Fancy dragons. These function much like any other goal card you’ve ever been dealt out at the beginning of your favorite euro game. They provide a small bit of direction, especially in initial plays, by providing concrete bonuses for doing specific things you probably would have done anyway. I like that part of them.

I do find some of the Fancy dragons to be a little underwhelming, though. Several of them have to do with the placement or amount of artisan dragons in shops at the end of the game. Even in a two player game, the amount of control you have over exactly where each dragon ends up feels fleeting. Sure you could devote time and effort to wrangling dragons where they need to be but the payoff does not feel worthwhile to me. My usual approach has been to ignore my Fancy dragons unless I just so happen to meet their condition. I don’t mean to say they’re weak– they’re probably not– just that I find them unfulfilling to pursue as an objective. For what it’s worth, my partner loves the Fancy dragons and says “I shouldn’t be allowed to score them” because of my denigration of their value.

One of the most interesting aspects of Flamecraft is the variety of shops. The initial six shops are always the same and they don’t have any special characteristics besides starting with a single dragon in them. However, once a shop is fully staffed, new ones will pop up at the edge of town. The abilities on these shops provide power exchanges or little buffs to entice you into the door.

A new shop might let you dole out food to the cards yet to be drawn, scoring points and making the “draw a card” action tastier for the next couple turns. Another might let you exchange victory points for the game’s wild currency, coins. Regardless, most shops reward heaps of points just for placing dragons into them, which means players are incentivized to visit even as the starter shops have more stocked shelves. None of these shops are ruinously complex, but they do pack a punch that keeps the game interesting going into its later stages.

Speaking of its later stages, I do like when and how Flamecraft winds down. When the enchantment deck or the artisan deck draws out, each player gets one more turn. At this point, the town square is overflowing with opportunities to get loads and loads of any kind of thing you want, but it hasn’t been at that stage long. By the time the game threatens to get unwieldy and too big for its own good, it ends. Also, because everyone has been building the engine together, there is rarely a situation where one player simply peters out. There will be a shop to go get a handful of points from, or an opportunity to fulfill a fancy dragon on the last turn. Everyone gets their own little slice of point paradise in Flamecraft.

Again, I do wonder if maybe we are all getting a bit too much of this paradise. This is a game without much tension or drama. It has, to me, a touch of the points-saladsy feeling of “everything I do nets points so kinda do whatever.” I have a fun time doing what I do in the game, but I don’t feel like I’ve carved my own path through it. Because of this, I like Flamecraft but I fall short of loving it.

I can’t end the review there though without giving just one more little shout-out to the world of Flamecraft. This is a world where little bread-type dragons sit in the delivery baskets of pizza delivery witches to keep the food warm. They have a dragon who sits on a waiter’s arm and brûlées the crème, folks. Look at this delicious potion being made by the proudest, quirkiest little wyrmling you’ve ever seen and tell me you wouldn’t tip them 50%. You can’t.

I’m happy to own Flamecraft because I’m happy to own inviting, friendly games. It tickles a part of my brain. I know I can show this to a new boardgamer at game night and it could easily become their new favorite game ever. That’s really cool, even if the game never rises above a gentle simmer.

Leave a comment